Art Deco and Art Nouveau were more than just artistic styles. They represented the powerful societal shifts that shaped the early 20th century. From Art Nouveau's fluid curves to Art Deco's geometric grandeur, the era left an indelible mark on everything from architecture to everyday objects. This article offers a taste of the impact and enduring fascination of these movements, drawing on material from our Art Appreciation Diploma course and dedicated module on Art Nouveau and Art Deco history.

In short…

This exploration of Art Nouveau and Art Deco’s history offers a glimpse into our Art Appreciation Diploma course, including a dedicated module on these groundbreaking styles.

Emerging in the late 19th century, Art Nouveau was a revolutionary "new art" movement that embraced fresh, modern aesthetics over historical styles. Instantly recognizable for its curved lines, organic forms, and elaborate floral patterns, many works were directly inspired by nature. The style championed asymmetry and flowing, sinuous lines, permeating architecture, furniture and {jewellery |jewelry}. Beyond just decorative, the influence of Art Nouveau sought to unify all art forms into a harmonious whole.

Art Nouveau formed as a direct response to the social, cultural, and technological shifts of the late 19th century. It sought to break away from academic traditions and mass-produced aesthetics of the Industrial Revolution. Its vibrant, naturalistic aesthetics drew inspiration from the Arts and Crafts movement and its emphasis on the handcrafted, and the visual asymmetry and natural motifs of Japonisme (Japanese art). It was a forward-looking style, but also deeply rooted in the desire for beauty and individuality in a rapidly changing world.

The term "Art Nouveau" originated from Siegfried Bing's Parisian gallery, "Maison de l'Art Nouveau," opened in 1895, which showcased this "new art" movement. While globally adopted, the influence of Art Nouveau also evolved under distinct regional names such as Jugendstil in Germany, Secessionstil in Austria, and Modern Style in Britain, reflecting its widespread yet local influence.

International exhibitions were crucial in propelling Art Nouveau onto the global

stage:

Art Nouveau was significantly shaped by the colonial influences and themes of exoticism. The fascination with newly accessible cultures led to designs incorporating Japonisme, Middle Eastern, and African art. These encounters broadened the style's visual vocabulary, but today are often viewed through a more critical lens, acknowledging the complex power dynamics of the era.

Art Nouveau's rapid ascent was in part due to advertising and commercialism. The style lent itself to posters, product packaging, and branding, transforming everyday objects into works of art. Key artists and designers like Alphonse Mucha and René Lalique (see his Dragonfly Woman Corsage, below), were masters of promotion themselves, skillfully shaping public perception to ensure Art Nouveau became synonymous with modernity and sophistication across Europe and beyond.

Art Nouveau transformed 20th century design movements, ushering in a new era for interior design, furniture, and decorative arts. Rejecting rigid historical forms, it embraced organic fluidity, evident in iconic pieces like the ornate Tiffany lamps and sinuous furniture by Louis Majorelle. This style infused everyday objects with artistic beauty, radically impacting the style of homes, textiles, and glassware across the globe.

Art Nouveau architecture profoundly reshaped the urban landscape, introducing organic forms and intricate detailing to traditional cityscapes.

Art Nouveau artists profoundly impacted visual arts, infusing painting, illustration, and sculpture with its distinctive organic and symbolic aesthetics:

Art Nouveau emerged during a period of political and social upheaval, an in doing so, reflected the era's anxieties and hopes. It represented a revolt against the impersonal nature of rapid Industrialization, urbanization, and the material conditions that characterized the late 19th century. Through its organic forms and handcrafted aesthetics, the movement subtly championed individualism, social reform and a return to nature.

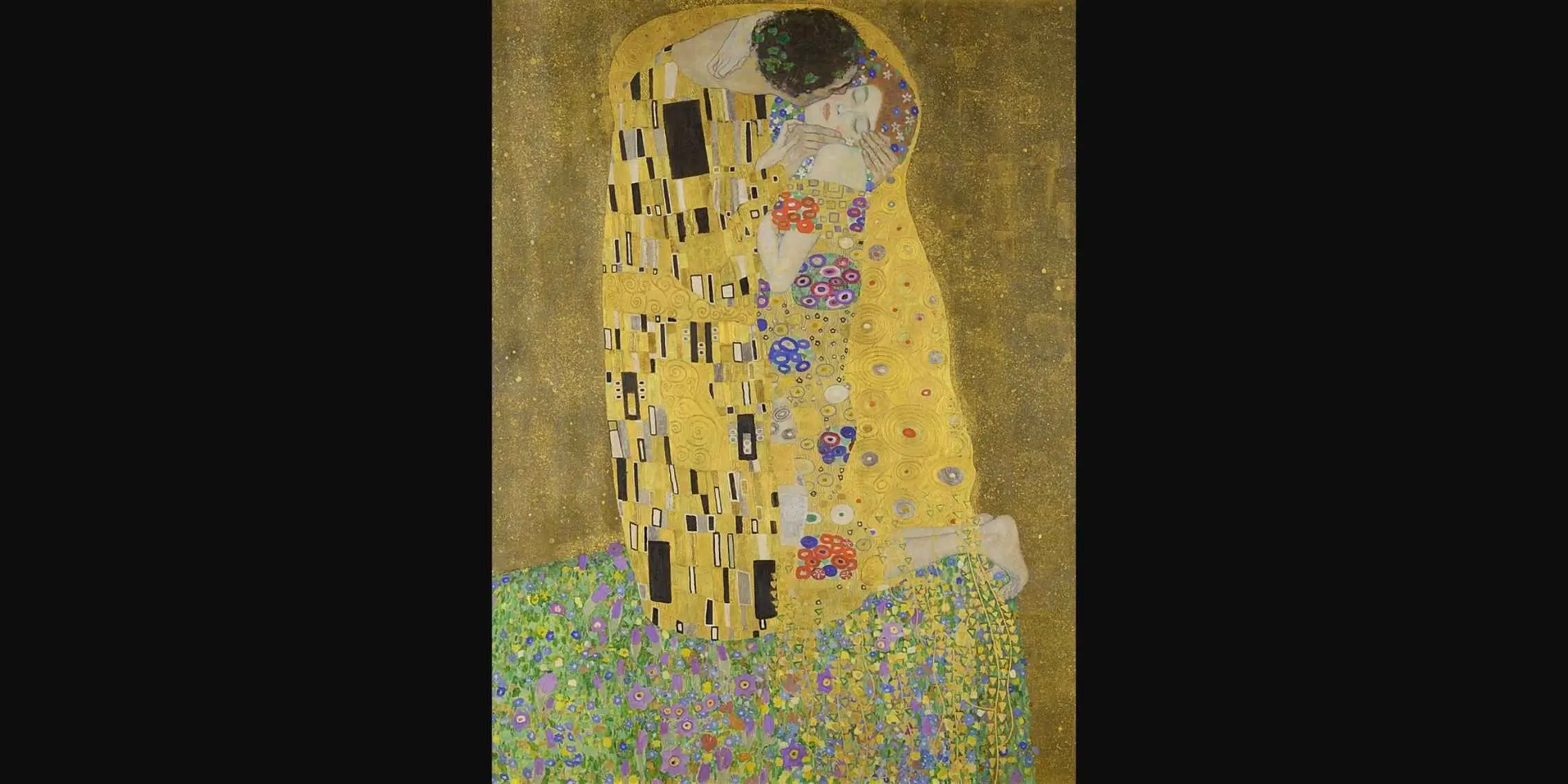

Art Nouveau frequently explored themes of eroticism and the human body, with many artworks featuring overt sexual undertones - such as Tamara de Lempicka’s

La Dormeuse, below. This fascination reflected broader cultural shifts, including burgeoning feminist ideas and changing perceptions of gender roles during the fin de siècle. The style's fluid lines and organic forms proved ideal for depicting sensuality, often showcasing idealized female figures as central, symbolic motifs.

Despite its reaction against Industrialization, Art Nouveau was paradoxically shaped by technology. New industrial techniques allowed artists to manipulate materials like wrought iron and glass with unprecedented fluidity, creating distinctive curvilinear forms that characterize the style. Embracing modern manufacturing methods enabled the widespread production of Art Nouveau designs, bridging the gap between art and industry.

While a global phenomenon, Art Nouveau adapted to many different cultural contexts, resulting in distinct regional styles across Europe:

By the early 20th century, Art Nouveau began to decline, partly due to its expensive, handcrafted nature and impracticality for mass production. Public taste also shifted, growing tired of its elaborate ornamentation and embracing a desire for simpler, more modern forms. This paved the way for the emergence of Art Deco, a more streamlined and geometric style that better suited the industrial age and its new, fast-paced modernity.

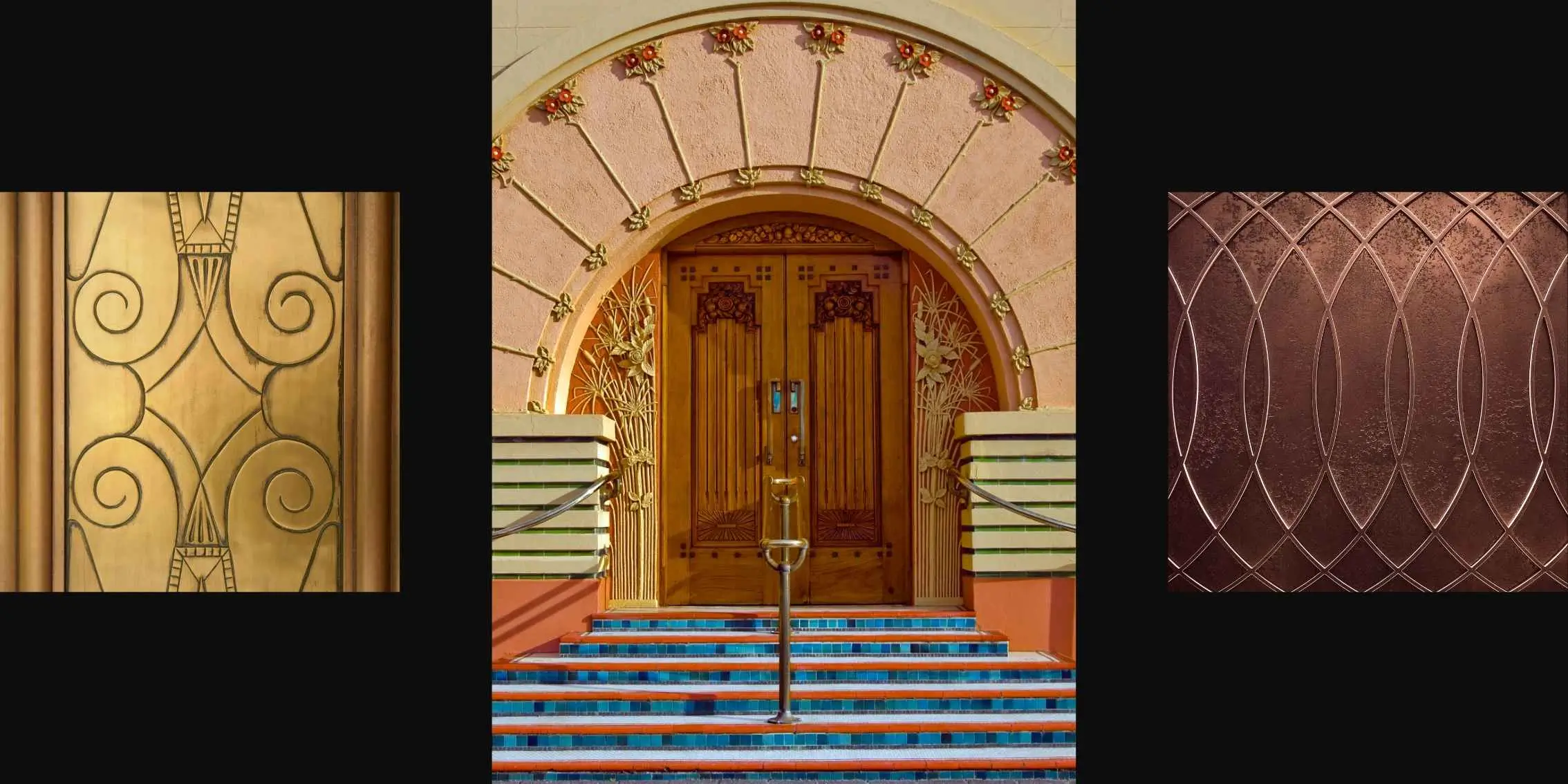

Emerging as Art Nouveau declined, Art Deco presented a distinct contrast, embracing the sleekness of the modern age. This style is defined by its characteristic geometric shapes, streamlined forms, and a celebration of luxurious and exotic, materials. Art Deco style elements captured the essence of modernity, reflecting the era's fascination with speed, technology, and glamoracross architecture, fashion, and decorative arts.

Art Deco emerged in the early 20th century and was profoundly shaped by the Industrial Revolution, the aftermath of World War I, and rapid technological advancements. Its aesthetic was largely cemented by the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, a pivotal event that showcased the style's emphasis on luxurious materials, craftsmanship, and a forward-looking vision. This new movement perfectly captured the era's optimism and desire for both elegance and efficiency.

The term "Art Deco" wasn't coined until 1925, taking its name from the influential Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris. The name cemented Art Deco's identity, showcasing its love for decorative arts, industrial flair, and an unmistakable modern look that quickly captured the cultural imagination.

International exhibitions were pivotal in launching Art Deco style elements to global prominence, embedding its sleek modernity into popular culture:

Art Nouveau's rebellion against Industrialization and Art Deco's sleek modernity redefined 20th-century aesthetics. Both styles, despite their distinctions, powerfully illustrate art's response to alienation – Art Nouveau seeking solace in nature, Art Deco embracing the machine age. Their revolutionary spirit still shapes contemporary aesthetics, modeling how social, political, and creative ideas intertwine.

Ready to discover more of art’s rich history and what it means to you? Our online Art Appreciation Diploma course offers deep art history knowledge, flexible study, and expert tutor support. No prior experience is necessary. Download your free prospectus today and begin your art journey.

Tutor at The Art Institute

At The Art Institute, our professional tutors provide clear, practical insights to help you appreciate and understand art and its historical context on a deeper level. Art experts like Stephen Farthing guide students of our online art appreciation course through each of several important movements throughout art history, such as the Art Deco and Art Nouveau movements.

Published: